|

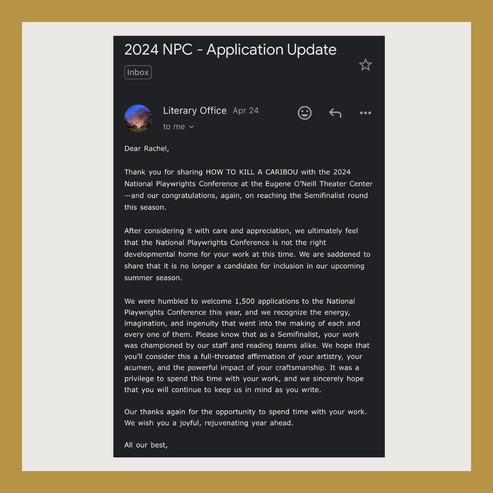

I, along with roughly a hundred other playwrights who were listed as semi-finalists, received our O’Neill National Playwrights Conference rejection email for my play How to Kill a Caribou. The institutions that produce these playwriting competitions typically send an email rejection letter. The National Playwrights Conference’s email was sincere and empathic. It states that we playwrights should be proud of making it to the semi-finals. People at O’Neill championed our work. And the fact that we made it to a select group of 250 plays out of 1500 that submitted is, “a full-throated affirmation of your artistry, your acumen, and the powerful impact of your craftsmanship.” I am grateful. I am proud of myself. But what now? If you’re unfamiliar with the National Playwrights Conference, here’s the gist. About the O'Neill National Playwrights ConferenceThe “O’Neill,” is one of many playwriting competitions. This particular playwriting competition has been around since 1964 developing plays from some of the biggest names in playwriting like Dominique Morisseau, Martyna Majok, Beth Henley, and Samuel D. Hunter — many of whom have gone on to win the Pulitzer Prize, Obie, and MacArthur awards. The O’Neill Playwrights Conference is a premier developmental opportunity for fresh, new plays that have never been produced. It is a chance for playwrights to collaborate with leading theatre professionals, workshop plays, network, and potentially, launch their careers. What happens after rejection?What happens to all those plays that didn’t advance? Whenever playwriting competitions reveal to me how many applications they received, I can’t help but get this feeling of dread. I think about a playwriting friend who asked, “What does that mean for the state of the theatre industry that they don’t have space for everyone?” Where are those plays supposed to go? Unfortunately, many plays will be tucked away in a desk drawer or filed in a computer folder labeled “Old Plays.” I don’t think it has to be that way. I'll explain how theatres, festivals, and institutions can help support new plays after rejection. Give me the cue-to-cue

What is new play development in playwriting competitions?New play development is the support of new theatrical works. The support can be: Financial: A theatre provides funding to the playwright or team of artists so they may focus their time and energies on the creation of the new work. Why is this important?: Many playwrights have to juggle full-time jobs on top of their artistic endeavors. Having the financial freedom to dedicate 100% of your time to writing your play helps reduce burnout and increases writing productivity. Developmental support: A playwriting competition provides the playwright with the tools, space, structure, and resources needed to develop their new play. Why is this important?: Often referred to as new play development festivals, new play workshops, or play readings, these opportunities give playwrights access to resources they might not be able to find on their own. Theatres tap into their networks to bring together directors, dramaturgs, stage managers, actors, designers, etc. The playwright now has a set period to work on their play aided by the professional advice of other artists. We can see the play on its feet while actors read lines in front of an audience. Promotional support: A theatre company, network, or institution increases the new play and playwright’s public awareness (brand awareness) through marketing and advertising. Why is this important?: Word of mouth is often the best form of advertising. Recommendations and reviews go a long way in theatre. If one theatre hears from another theatre that a play is worth their time, there’s a higher probability they will consider working on the play. What challenges do playwrights face?I shared a few challenges playwrights face above — financial freedom, access to resources, and limited to no brand reach. For me, one of the biggest challenges is playing a game of numbers. I’m not even talking about competition. Healthy competition breeds better writing. Most playwrights are taught to get used to rejection. You’ll submit to 100 playwriting competitions in a year and maybe be accepted into 5-10 of them (maybe). Sometimes you might not be accepted at all. I’ve previously shared why playwrights should not let rejection get them down. You don’t need to wait for anyone’s permission to share your voice. If you get rejected, move on and find collaborators who see the value in your work. But let’s dig into rejection for a moment. Why are the odds not in our favor? I’ll use the O’Neill National Playwrights Conference as an example. Why rejection might happenFifteen hundred new plays were submitted. Think about that number. Picture 1500 pencils. 1500 apples. 1500 cats. It’s a lot. Now, think about 1500, but it’s plays. Full-length plays. A typical full-length play is 60 - 120 pages. For the sake of this example, let’s say every play was 90 pages. 1500 plays at 90 pages each is 135,000 pages total. Have you ever read anything that was 135,000 pages? Now, of course, the O’Neill uses teams of play readers that divide up the plays so it is much more manageable. No one person is reading 135,000 pages in one sitting. That is still a ton of work. And play readers are people. They have opinions, tastes, favorite and hated genres. They get overworked and tired. They have bad days and good days. I often joke that when I’m rejected, it’s because the person reading my play spilled coffee all over their white shirt, got a speeding ticket, stubbed their toe, and then had to read my play which was number 18 out of 20 for the day’s quota. It’s all subjective. What do we do with 1500 new plays when we only have space for 8? Theatre companies across the globe are popping up, asking, searching, and demanding new plays to make their way onto stages. If theatres want to help new plays get produced, (that they cannot produce) here’s how. 3 ways theatres can support new plays and playwrights after rejection1.) Introduce the playwright to your network. I’ve been involved with so many festivals that said they loved my work. They just don’t have the (budget, resources, or audience) to produce it on their stage. What I would love to see them do is share my play with their network. Write an email, and recommend us to a colleague. Call up your people, put our plays in front of them, and tell them what you like about it and why it would be a good fit for their theatre. 2.) Write a review. There are various public platforms where you can provide your stamp of approval for the world to see. The New Play Exchange (NPX) is one of my favorites. It is an online platform that offers playwrights space to post their new plays for theatre companies to download and read. If you like a play, you are encouraged to leave a positive review. You can also write a review on the playwright’s Facebook page, YouTube, or blog. 3.) Be loud on social media. Follow, like, comment, and share the playwrights’ posts and social media profiles. It takes a simple tap of the heart icon. Suddenly, the mystical algorithm promotes us to the public. Share our profiles and follow along on our journey as writers. Keep liking posts and stay connected even after the playwriting competition is over. Share the network powerYou can do any one of these things together or separately. Mix and match. Look, I get that budgets are tight and stage space is limited. But don’t underestimate the power you have through your network and your own institutions’ prestige. There are 1500 new plays out there and that’s from just one competition. Help keep as many of those new plays from ending up stashed away and forgotten. Comments are closed.

|

About the BlogI write plays. I tell stories. I create content. I vent. I offer advice. I hope people will learn from my mistakes. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed